How Rapid Wetland Loss Is Rewriting the Climate of India’s Tier-2 Cities

Introduction

Every monsoon in Guwahati’s Ambikagiri Nagar, the pattern is predictable. Streets vanish under rising water, families stack belongings on higher shelves, and power cuts arrive before the drainage can catch up. Residents insist the rain hasn’t changed – only the land has. The wetland that once absorbed their runoff was filled for construction. When it disappeared, so did their protection.

Thoreau once asked, “What is the use of a house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it on?”

He wrote this more than a century ago, but the warning fits the reality of India’s Tier-2 cities with uncomfortable accuracy. As urban growth accelerates, the wetlands that kept neighborhoods cooler, safer, and water secure are vanishing. The result is not a slow environmental shift but an immediate disruption to heat, flooding, and daily life.

What Urban Wetlands Actually Are

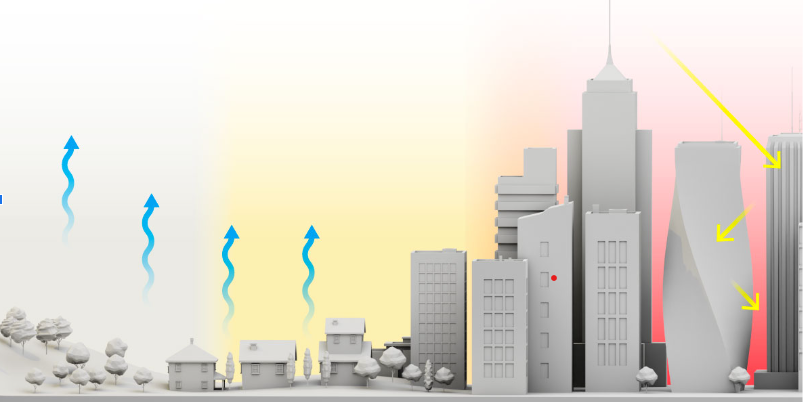

Urban wetlands are not empty spaces or leftover land. They are the city’s natural climate infrastructure which includes lakes, tanks, marshes, and low-lying basins that move, store, and regulate water.

They silently perform these four essential functions:

- Hold excess monsoon water, preventing rapid flooding.

- Recharge groundwater, keeping wells and bore wells alive.

- Cool surrounding neighborhoods through natural evaporation.

- Release pressure on drains, reducing sewage overflows.

When wetlands are replaced by concrete, these protective systems vanish instantly. Cities heat up, runoff accelerates, and drainage fails during routine storms.

A Pattern Repeating Across India

India has lost almost 30% of its wetlands in three decades, according to the (Wetlands International South Asia report). Tier-2 cities not only urbanize faster than they can regulate, but also they are losing them even more rapidly.

Guwahati, Assam

The lone Ramsar site has shrunk, due to dumping, railway line and encroachment (Deepor Beel). The surrounding communities, that once drained well, stay underwater through moderate rain events.

Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu

Trapped between construction and debris, the ancient lakes of Singanallur and Kumaraswamy have lost their potential to hold stormwater and cool the city.

Indore, Madhya Pradesh

The wetland areas surrounding Pipliyapal Lake and the channels bringing water to it and Sirpur Lake and its feeder streams, have been affected due to housing complexes. Due to which, Groundwater recharge has reduced drastically.

Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh

Despite its “City of Lakes” identity, buffer zones around Upper Lake and connected wetlands face persistent encroachment.

Across cities, wetlands are treated as convenient land banks until their absence becomes costly.

How Tier-2 Cities Are Losing Their Wetlands

Construction fills natural water basins

Developers use soil and construction waste to flatten wetlands so they can build on them, erasing the natural spaces that once held rainwater.

Paperwork reclassifies ecological zones

Once a wetland is labeled “developable,” its destruction becomes legal, fast, and irreversible.

Inflow channels are blocked

Roads, garbage dumps and unplanned settlements choke the waterways that feed wetlands, cutting off the flows that keep them alive.

They are not accidental losses. They are deliberate choices that erase a city’s natural resilience.

Street-Level Consequences

1. Hotter neighborhoods

Lost wetlands remove natural cooling. Affected areas often record 3-5°C higher temperatures.

2. Faster, deeper flooding

With no storage basins, rainwater moves directly into streets and homes. Flooding now forms within hours.

3. Declining groundwater

Recharge zones vanish, wells fail, and families turn to expensive tanker water.

4. Rising household costs

More heat means longer hours of fans and ACs. Scarcer water means higher supply expenses.

5. Drainage and sewage breakdowns

Wetlands once absorbed overflow, without them, even modest rainfall triggers backups.

These impacts hit households long before they appear in climate assessments.

Human Impact

1. Vineetha T.V., Panangad (Kochi)

Without transferring titles for the land, a wetland in Vineetha’s vicinity near her home was filled and plotted to real estate, leading to it gradually sinking the ground, upon which Vineetha’s house stood. A once-solid, dry neighborhood now floods every time there is heavy rain. Water leaks through her floors, dampens her walls for weeks, and the groundwater that sustained her family went from clear to murky. The wetland that shielded her home for decades is no more, and the damage is irreversible.

2. Residents of Ambikagiri Nagar, (Guwahati)

In Ambikagiri Nagar, nearly 50,000 people live with the consequences of erased wetlands. Every monsoon, streets turn into waist-deep pools within hours. Families stack furniture on bricks, spend nights draining water from their homes, and watch their belongings rot each year. The natural basin that once kept this neighborhood safe was built over, and the flooding that replaced it has become a defining part of daily life.

____________________________________

Times of India:illegal wetland filling in Panangad.

Times of India:waterlogging in Ambikagiri Nagar.

These stories show how environmental loss becomes household loss.

Case Studies

Case Study 1: Guwahati, Assam

Location: Deepor Beel floodplain

Change:With respect to Deepor Beel, the years of dumping, railway expansion and creeping development have gradually reduced its ability to hold monsoon water.

Mechanism: People in charge and companies developing the area didn’t consider the Deeper Beel to be anything more than vacant space, which meant that construction and littering went ahead without a hitch.

Impact:

Persistent and widespread waterlogging in surrounding neighborhoods.

Slower drainage after even moderate rainfall.

Noticeably higher local temperatures as open water and vegetation disappear.

Significance:Weakening a Ramsar wetland like Deepor Beel dismantles the whole natural flood defence system, putting the city at the mercy of severe flooding and heat waves.

___________________________________

Marxen, R., & Gupta, U. (2021).

“Urban wetland shrinkage and its impact on flood risk: Deepor Beel, Guwahati.” Indian Journal of Ecology.

Dutta, P. (2022, August 24).

“Untreated legacy waste is polluting the sensitive wetland ecosystem of Deepor Beel.” Mongabay India.

Case Study 2: Indore, Madhya Pradesh

Location: Sirpur Lake, Yashwant Sagar

Change: Rapid peripheral development has squeezed buffer zones and blocked natural inflow routes, limiting how these wetlands function during rainfall and dry seasons.

Mechanism: Urban expansion moved faster than environmental regulation, allowing builders to narrow channels and occupy critical recharge areas without consequences.

Impact:

Sharp decline in groundwater recharge across expansion zones.

More severe summer heat due to lost moisture and evaporative cooling.

Increased surface runoff during monsoons, overwhelming local drainage.

_________________________________

Times of India. (2023).

“Indore and Udaipur join list of Wetland Accredited Cities.”

Singh, A. (2022).

“Impact of urbanisation on wetlands and climate resilience in Indore.” Journal of Urban Studies and Planning.

Significance: Earning the title of “Wetland City” becomes meaningless when protective rules are ignored and the gap between global recognition and actual resilience continues to widen.

Both cities reveal the same truth : once wetlands are weakened, the surrounding urban system collapses, and no amount of recognition or planning can compensate for physical loss.

Solutions for Tier-2 Cities

1. Protect

- Legally map all wetlands and enforce no construction buffer zones.

- Halt land use conversions that convert wetlands into real estate parcels.

2. Restore

- Reopen blocked inflow and drainage channels.

- Desilt wetlands and revive native vegetation.

- Reconnect isolated wetlands to natural water networks.

3. Govern

- Impose strict penalties for dumping.

- Integrate wetlands into city master plans as hard infrastructure.

4. Mobilize Communities

- Build public understanding that wetlands are essential city assets.

- Support citizen mapping, monitoring and reporting systems.

- Encourage local participation in restoration and cleanup efforts.

Without these actions, the financial and climate costs will escalate each year.

Conclusion

The loss of wetlands is not a “nature” issue. It’s a climate issue, health issue, flood issue and in the end it’s about survival.

Wetlands are the air conditioners of cities, reduce floods, recharge water and protect our homes. Remove them and the results are swift: hotter streets, deeper floods, wobblier water supplies and more expensive households.

For India’s Tier-2 cities, this is not a debate between nature and development.

It’s a choice of short-term construction profits or the long-term survival of the city. There is no path to a livable future if wetlands are destroyed. It is no surprise that cities now focus on protecting and restoring them, because without wetlands, there is no future.