Why Our Cities Are Getting Hotter: The Hidden Heat We Built Ourselves

Walk down a busy Indian street in the late afternoon and you’ll notice something off. The heat isn’t just overhead, it's rising from the pavement, bouncing off buildings, and sticking to your skin long after sunset. By 10 pm, the air can still feel like it’s holding on to the day.

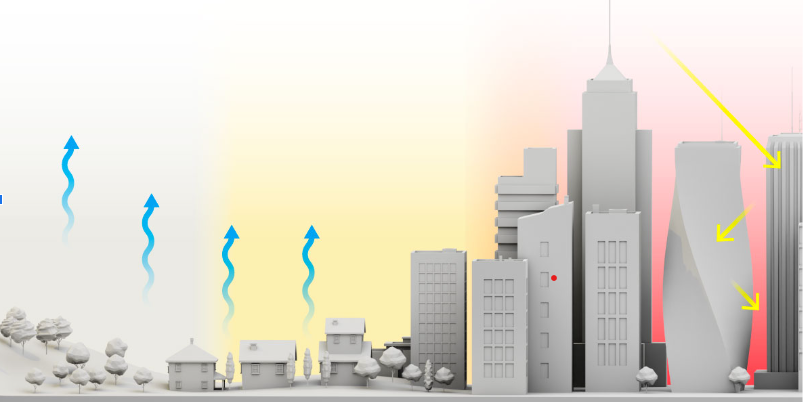

This isn't an ordinary summer. It’s the heat island effect, a climate our cities created without meaning to.

Over the past two decades, Indian cities have warmed 2–3°C faster than nearby rural areas, according to the Indian Meteorological Department. Satellite images now show dense urban pockets glowing hotter than their outskirts almost every single night.

None of this happened in one big moment. It happened the way most changes in our cities do: slowly, through decisions that felt minor or convenient at the time.

1. How Concrete Turned Cities Into Heat Batteries

If you stand barefoot on soil and then on a concrete pavement, you’ll understand the whole problem immediately. Soils cools quickly and even help in reducing the heat in certain circumstances. But

Concrete holds onto heat like a tawa that refuses to cool even after the flame is off.

The Centre for Science and Environment estimates that up to 65% of the surface area in major Indian cities is now paved, much of it with materials that trap solar heat.

Walk near any flyover in the early evening, say the stretch under the pillars in Bengaluru or the market lanes in Delhi and you’ll feel that stored heat rising from the ground. The sun may have set, but the pavement is still radiating the day back at you.

2. The heat line effect

Every flyover, building, and road begins with sand, the riverbed kind we’ve been scooping out faster than nature can replenish. India pulls out so much of it each year that some river communities have literally watched their banks crumble away. In parts of Kerala and Bihar, homes that once stood a few metres from the water now sit at the edge of nothing.

When you scrape away wetlands and river edges, you lose the natural shade and moisture that keeps nearby areas a little cooler. So the heat rises, bit by bit.

Then comes cement. It’s hot to produce and even hotter to live around. Anyone who’s walked under a new flyover at 11 pm knows the feeling, the concrete radiates like it’s storing the afternoon inside it.

We ended up building Indian cities with materials that make sense in cooler countries, not in a place where summers already push 40°C. We sidelined older, climate-friendly methods like lime plaster, porous bricks, and jaali designs that used to let buildings breathe. Now our structures lock heat in instead of letting it escape

3. Glass Buildings That Fight the Climate Instead of Working with It

Glass towers became symbols of prosperity. But in a tropical climate, they behave more like greenhouses.

Studies suggest that fully glazed buildings can end up using far more cooling energy than places built with shade, ventilation, and sensible window design.

You don’t need the numbers to feel it. Walk near one of those mirrored office blocks on a hot afternoon and your face catches the reflected heat like a blow dryer. The building’s glass bounces off the sunlight straight onto the pavement, and even those rows of AC units at the back pushes warm exhaust into the street.

Inside, it feels cool and civilized. Outside, that comfort has a cost: the building is dumping its heat into the very city already struggling to breathe.

4. When Ponds Become “Empty Land”

5. The Vanishing Shade We Didn’t Notice

6. Heat Waves Hit Everyone, But Not Equally

Heat waves are more frequent and more intense, with some parts of India now getting twice as many extreme-heat days as in the 1980s, according to the IMD.

But the heat doesn’t punish everyone the same way.

Homes That Trap Heat

Homes with tin roofs in informal settlements routinely reach temperatures far higher than the weather report.

Step inside at noon and you feel it immediately: air that stings your skin, floors too hot to sit on, walls radiating heat long after sundown.

Work That Can’t Pause

People who live in these places can’t “stay indoors” or “avoid peak hours.”

Missing a shift means missing income.

You’ll see a worker wrapping a soaked towel around his head before cycling to the factory, hoping it buys him another hour before dizziness kicks in.

What Heat Does to the Body

Dehydration doesn’t show up as a medical term — it hits as pounding headaches, nausea, sudden fatigue, dark yellow urine, and cramps that stop you mid-step.

Kidney stress isn’t a distant diagnosis, it’s the burning sensation when you pee, swelling in the legs, and a constant thirst that never feels satisfied.

Power Cuts That Make it Worse

Power cuts during the hottest hours trap families in rooms that feel like metal containers left on a stove.

No AC, no backup, sometimes not even a working fan.

When Cooling Becomes a Privilege

Cooling becomes a privilege.

Not in theory in small daily choices.

Like a working mother deciding whether to run the fan all afternoon or save the electricity money for school fees, while her child naps in air that never cools.

Shade becomes a privilege.

Rest becomes a privilege.

Even surviving summer without harming your body becomes a privilege.

7. What Can Actually Cool a City without Waiting 50 Years

The good news? Cooling doesn’t need decades.

A lot of it can happen in a single summer if we bring in the small changes.

Cool roofs mean cooler sleep.

When roofs are painted white or fitted with reflective sheets, indoor heat drops by a couple of degrees.

Telangana found that families actually slept better and used fans less during their pilot, which is a real win in a city where power cuts hit at night.

Permeable streets stop waterlogging and heat build-up.

Roads that let rainwater sink in cool faster and don’t flood every monsoon.

Indore used these around markets and bus stops so people weren’t standing ankle-deep in dirty water while the evening heat baked the asphalt.

Buildings designed for shade cut bills and stress.

Smaller glass facades, louvers, cross-ventilation, trees right outside basics that stop homes from turning into ovens.

Ahmedabad pushed this in its heat action plan, and households reported lower electricity bills instead of depending on ACs 24/7.

Water bodies cool neighbourhoods.

A pond or tank can take the edge off the heat in a one-kilometre radius and keep groundwater alive.

Bengaluru restored a few lakes and saw nearby colonies go from suffocating heat to evenings where people could actually sit outside without melting.

None of this is futuristic.

It’s routine work that matters because people feel the difference immediately better sleep, less waterlogging, lower bills, cooler evenings.

References

1. Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), Urban Heat Island Studies, 2020–2023

2. Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), State of India’s Urban Environment, 2022

3. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Urban Climate Chapters, 2021

4. Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), Glazing and Building Energy Use in India, 2019

5. Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), Tamil Nadu Report on Waterbody Encroachments, 2019

6. World Bank, Climate Change and Urban Heat in South Asia, 2021

Visuals sources

1. https://share.google/images/ur4nckuIXrGb4gvhH

2. https://share.google/images/DJrtJPn3OCv9prwHU

3. https://share.google/images/XnDy2I5rDIYRysmYf

4. https://share.google/images/Mbj5KXYOL446if1Zn

5. https://share.google/images/F6VeTS6eFINzu8xGB

6. https://share.google/9kFQAONsEhyDHbv5u