The Electronic Graveyard: Why India’s E-Waste is a Goldmine Disguised as Garbage

The informal economy pumps the income of a large chunk of India’s citizens and constitutes nearly 45% of the national GDP. One such example of a booming informal sector lies in the suburbs of east Delhi. The area is called Seelampur and is considered to be India’s largest e-waste dismantling market.

A fourteen-year-old boy, Irfan sits in a dim workshop in Seelampur. Around him, heaps of broken laptops, chargers and motherboards rise like metallic hills. He can be seen cracking open a dead smartphone with the speed of a surgeon. He has never owned one, yet he dismantles dozens daily and, in the process, he ends up breathing fumes, sorting scraps and uncovering bits of the precious items within.

What looks like a waste to most of us is Irfan’s world, it is an everyday treasure to them. Inside each rusting laptop and cracked phone lies something we rarely think about: gold, silver, cobalt, copper, tin, titanium, palladium and reusable circuits. For years, this market has been home to thousands of informal workers who spend nearly 10 to 12 hours a day extracting valuable metals and electronic parts from the devices.

In fact, buried inside India’s e-waste is an entire hidden economy, which fuels the livelihood of many like Irfan and his family. This story is just an example of how people depend on e-waste now, as a form of livelihood and how places like Seelampur and other cities such as Kolkata, Mumbai and Bengaluru are emerging as India’s growing electronic graveyards.

But just because it holds an importance in the lives of many workers does not automatically enshrine e-waste in a position of being something valuable in the long run. The truth is it is still harmful. According to a UN report, India is the world’s fifth largest producer of e-waste and generates approximately 6–7% of the world’s total. A lot of the e-waste produced is either burned or dumped in landfills.

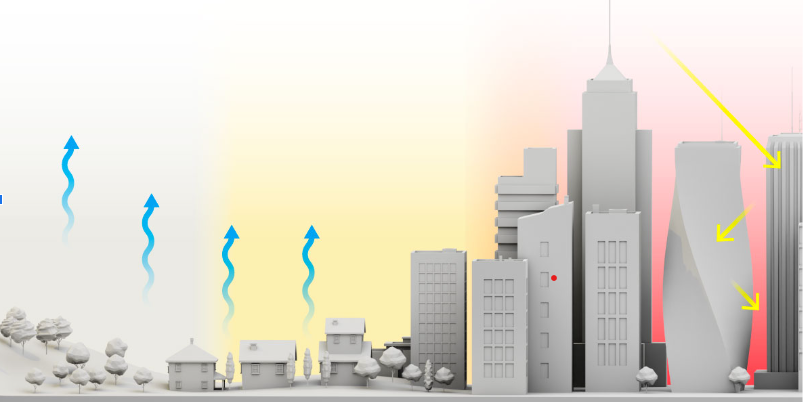

With the situation of rapid urbanization, the amount will only multiply as technology, digital knowledge and production of devices are increasing in a digitized world. Even the ones who pick the waste are having a risk to their health as their work exposes them to ever higher levels of pollution and dangerous toxins.

Where Does India’s E-Waste Actually Go?

With the huge amounts of e-waste produced annually in India, only a small fraction of it seems to be passing through formal recycling channels. The rest flows into:

- Informal recycling hubs: Informal waste pickers help clean up India’s cities by recycling approximately 20% of the waste generated, but still lack formal recognition, equal rights and secure and healthy livelihoods. Places like Seelampur in Delhi and Mumbra in Mumbai dismantle electronics using and recover valuable metals, albeit unsafely without proper safety or environmental concerns.

- ‘Kabadi Networks’ that don't get enough credit: Kabadi networks form the frontline of India’s circular economy, with neighbourhood scrap dealers collecting old routers, broken TVs and discarded cables that might otherwise end up in landfills. Yet despite their crucial role, this vast network operates without formal training, safety standards or institutional support, hence the focus needs to shift.

- Landfills that become time bombs: Areas like Bengaluru’s Bellandur and Delhi’s Ghazipur are filled with e-waste that leaks harmful substances like mercury, lead, and microplastics into soil and water and are paving way for long-term health effects.

Irfan’s story in Seelampur is an example of how much e-waste tends to flow outside of formal systems and how these nodes of recycling have become more prominent in the business.

E-waste or a Resource?

E-waste recycling, despite its many flaws, remains an important source of income for many. A surprising fact is that a tonne of e-waste contains nearly 100 times more gold than a tonne of mined gold ore, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. The electronics we throw out are actually hidden mines of metals and reusable components like screens and chips. These can be reused in new electronic devices or repurposed entirely. Thanks to government regulation like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and a rise in business from recycling, there’s also money to be made in just processing the materials and if recycled properly, India could unlock a goldmine and reduce dependence on imports for electronic parts. E-waste and battery recycling represent a $7-10 billion market opportunity in India over the next decade. As Rahul Singh, business head at Exigo Recycling, notes that this potential remains mostly untapped despite rising volumes.

So What’s Going Wrong?

The ever-increasing e-waste in India presents a significant economic opportunity. But it remains informal to a large extent, with the pressure on workers like Irfan and his family.There is a need for a structured and sustainable e-waste management. A few problems that this sector faces are:

- The informal sector does 90% of the work, but without safety: Workers extract metals using rudimentary methods that expose them to health risks. These practices, such as burning plastics, spread the pollution locally too.

- Slow or Broken Supply Chain: India has over 400 registered recyclers but many operate at half the capacity because e-waste hardly reaches them. The flow of the primary product, which is discarded electronics, is broken as the collection system is lacking behind.

- Consumers don’t know what to do: Many households simply store old gadgets or hand them to neighbourhood Kabadiwalas, reflecting the absence of accessible or well-aware disposing options.

How can we actually turn the Electronic Graveyard into a Profitable business?

What is important for us is to recognise that the informal sector is an important part of the solution for trying to solve the problem of e-waste. They are India’s urban miners who can already recover precious metals with remarkable efficiency. What extra they need are: tools like safety equipment and protective gear, training for safe dismantling and proper segregation techniques and integration with formal recyclers.

We can also try to build a hybrid model which respects local level participation. This model can include both public authorities responsible for waste collection as well as:

- local collectors and small shops for e-waste pickup from doorsteps.

- The collectors can be trained and certified for their services.

- This preserves incomes and improves e-waste recovery rates.

There is also a need to promote a repair-first culture. By supporting repair shops and refurbishers with easy access to spare parts, India can extend the life of electronics and slow down the flow of waste.

A solution at a large scale level, specifically to address the problems of rapid e-waste accumulation in the metropolitans of India, can be to build “Urban Mining Centres”. They can be dedicated recycling hubs equipped with advanced technology that can extract gold, copper and rare earth metals at an industrial level. These parks reduce environmental damage and boost domestic manufacturing, turning what we currently burn/bury into an alternate economic resource.

Hence, Irfan’s story shows that India’s e-waste isn’t just discarded tech, but a livelihood for thousands. But without awareness and responsible recycling, this overlooked, informalised economy will remain environmentally dangerous and financially undervalued. With the right support, e-waste can shift from hazardous material to an engine of circular growth.

Image Citations

https://www.dw.com/en/india-electronic-waste-provides-poor-children-a-dangerous-living/a-64656699

https://restofworld.org/2025/india-e-waste-recycling-electronics/